Medical intelligence is a critical capability for monitoring and assessing health risks, operating within a framework that prioritizes military considerations, and constituting an important element of national security.

Over the years, the fields of medical intelligence, security and global health have become interconnected, with a long history of growth after infectious diseases, vaccines, environmental threats, zoonotic diseases, medicines, and laboratories began impacting global security agendas in various ways. Intelligence, security and global health are distinct yet interrelated domains, with a long history of overlapping priorities and often conflicting interests. In recent years, the impacts of these sectors have been particularly prominent on the international stage, as disease and insecurity have become increasingly intertwined, as a result of the spread of the covid-19 pandemic and its repercussions on the world. The role of medical intelligence in securitizing diseases and epidemics has been especially prominent, given how the characteristics of infectious diseases can spur the spread of contagions affecting military operations and strategic or political interests of societies and countries. This new idea suggests that contagious diseases can not only prolong conflicts but also accelerate them. Additionally, they shape policymakers’ consideration of health as part of security agendas.

The rationale for securitizing disease has been largely based on the ability of disease outbreaks to undermine the relative power of the state, especially during periods of conflict. Thus policymakers have recognized the destabilizing threat posed by infectious diseases and the impact that the failure of health systems can have on peace and global stability. This rationale adds another layer of complexity to the standard definitions of security as a form of power that largely aligns with definitions of global health. By this definition, practically any state of poor health could warrant securitizing disease due to its ability to weaken human capabilities, especially given that health risks to individuals can swiftly become risks to entire populations. However, in practical application, the security rationale does not focus on disease-affected communities but rather its perceived threat to the international community, geopolitics and national security. This is consistent with the Copenhagen school’s definition of security threats as the existential threat to some object such as states, populations, or global networks of power.

A useful term can be borrowed from the World Health Organization (WHO) to identify health threats that should be incorporated into the security dimension, where a public health emergency of international concern refers to an extraordinary, unusual or unexpected event, with a serious and potentially international impact on public health. This definition allows for ignoring common and expected diseases, focusing instead on deadly diseases that can cause collective harm at the international level.

The Concept of Medical Intelligence

Medical intelligence is a type of intelligence information. It comes from collecting, evaluating, analyzing, and interpreting medical, biological, and external environmental data. This information is important for strategic planning, military medical planning, and operations that aim to maintain the health readiness of friendly forces. It also helps assess the medical capabilities of adversaries in both military and civilian sectors. In this framework, intelligence on diseases and epidemics constitutes a part of intelligence, which is why the United States places its National Center for Medical Intelligence within its Defence Intelligence Agency. Moreover, disease surveillance activities fall strongly within the jurisdiction of military organizations. This differs from NATO’s definition of medical intelligence, which defines it as an intelligence rather than a medical function, and thus can be operationalized for the benefit of national strategic interests. This definition primarily focuses on evaluating health infrastructure. While this is a relatively small domain within national intelligence structures, it is nonetheless important for its role in global surveillance systems. Furthermore, this sector engages in activities directly relevant to global health, yet maintains consistent priorities in line with strategic security interests.

This reinforces the utility of intelligence gained from studying every aspect of natural and human-made external environments that could impact the health of military forces. It can be used not only to anticipate the medical vulnerabilities of an enemy but also to provide adequate medical protection to friendly forces. Medical intelligence includes terrorist threats that have been applied in the civilian sectors, as it involves information used for the identification, characterization and management of risk applied to countermeasures in the civilian and military sectors against biological terrorism. Moreover, medical intelligence involves information related to threat detection and identification within the operational context and characteristics in the theatre of operations. Any individual operational detail could enable the commander to successfully execute the mission. Thus information useful for countermeasures, threat mitigation, and maintaining force health is classified as high intelligence priorities.

Medical intelligence typically derives information from various risk assessments (environmental, industrial, health, infectious diseases) from classified and open sources, public health centres, medical reports, and publications. While it may be difficult to distinguish between medical information and medical intelligence, the former tend to maintain a higher degree of certainty and be more firmly rooted in authoritative knowledge from health authorities and medical advisors.

On the other hand, medical intelligence refers to information containing more uncertainty. This information is more predictive in nature and is framed in the context of a specific process, to help leaders and policymakers assess potential repercussions of their decisions and avoid pitfalls. Thus medical intelligence turns into medical information when it is validated.

Wars & Pandemics

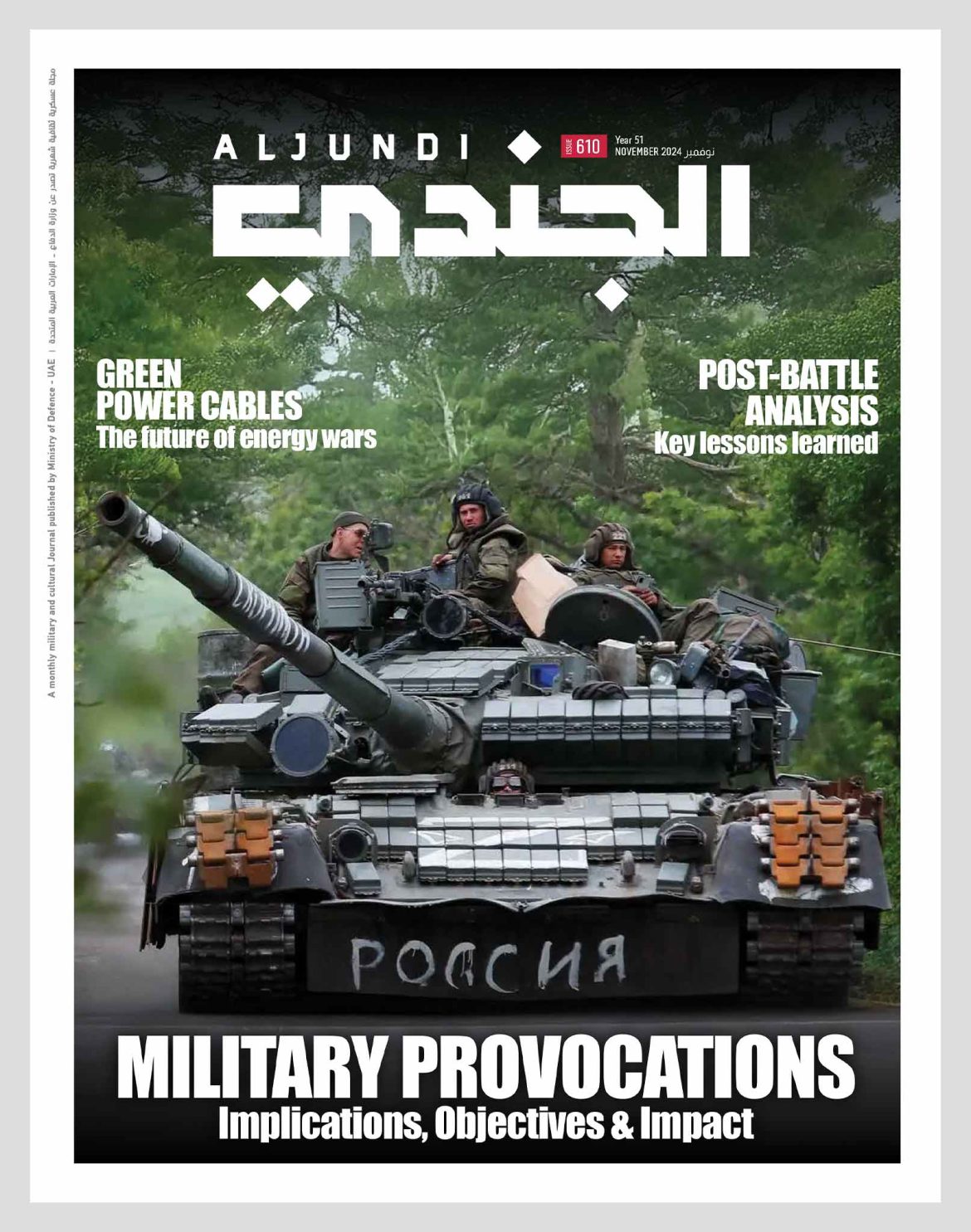

Pandemics have drained and destroyed armies’ ability to fight, halted military operations, and brought death and disaster to civilian populations of warring and non-warring states. The geographic spread of infectious diseases associated with wars throughout history raises the issue of how the distribution of diseases in epidemics has been affected by military operations. Historically, contagious diseases spread more during wartime and had a major impact on the course of operations. In 430 BC, when battles were raging between Sparta and Athens for dominance of Greece, Athens faced the plague in addition to Sparta. In the late Middle Ages, disease contributed to the fall of the Venetian Empire. During Napoleon’s wars, eight times as many people died in the British army from disease than from battle wounds. In the American Civil War, more than two-thirds of soldier deaths were due to pneumonia, typhoid, dysentery and malaria. The 1918-1919 Spanish flu pandemic killed more than World War I, with the death toll estimated at 20 – 40 million people. This was the highest recorded mortality rate for any epidemic and included 675,000 dead American soldiers who were crowded into trenches to hold the Western Front. As sick fighters returned, the epidemic spread like wildfire in the United States and affected a quarter of the population. On the Eastern Front, typhus, which was equally deadly for caregivers on the battlefield, caused 3 million deaths in Russia, Poland and Romania between 1918 and 1922. By the end of World War II, more soldiers had died from epidemics in wartime than from enemy actions. In 2014, medical intelligence was heavily involved in the rapidly deteriorating security and health situation assessments following the unprecedented Ebola outbreak in West Africa. Thus the role of medical intelligence structures was to assess the likelihood of the virus spreading, what that spread pattern would look like, what strategic threats were associated with it, and what the appropriate response should involve. NATO Medical Intelligence Centre (NMIC) participated in this activity and called for the incorporation of threats from non-governmental and non-human actors into its collective defence doctrine, specifically in response to the unfolding Ebola emergency. This constituted an important measure because it legitimized the use of NATO’s “collective response” which usually starts after specific “threats to peace” to support NATO force interventions.

A Small Domain with a Large Impact

Government actors have increasingly embraced the concept of disease securitization, encouraging the development and establishment of national medical intelligence bodies within military and civilian organizations. For instance, during the sustainable development goal-setting process, a proposal for a goal related to global health security was put forward as follows: “Take appropriate steps to limit the exposure of people around the world to new, acute or rapidly spreading risks to health, especially those that cross international borders.” Although this proposal was not adopted, it highlights the growing agenda of incorporating security into modern concepts of health. The work of medical intelligence includes epidemic diseases, environmental health, global health systems, medical science and technology, as well as health capabilities and capacities, which are categorised into the following four key areas:

● Environmental Health:

• Identifying and assessing environmental hazards that could lead to degradation of force health or effectiveness including chemical and microbial pollution of the environment, toxic industrial, chemical and radiological accidents, and terrorism/environmental warfare.

• Assessing the impact of external environmental and public health issues and trends on environmental security and national policy.

● Epidemiology:

• Identifying, assessing, and reporting on infectious disease risks that could lead to degradation of the deployed force mission effectiveness and/or cause long-term health effects.

• Alerting military and political leaders to disease outbreaks with national security implications, including intentional introductions.

● Life Sciences and Biotechnology:

• Assessing foreign basic and applied biomedical and biotechnology developments of military medical significance.

• Assessing foreign civilian and military pharmaceutical industry capabilities.

• Assessing external scientific and technological medical progress for defence against nuclear, biological and chemical warfare.

• Enhancing awareness of foreign technology.

• Preventing the proliferation of dual-use equipment and knowledge.

● Medical Capabilities:

• Assessing foreign military and civilian medical capabilities including treatment facilities, medical personnel, emergency and disaster response, logistic services and medical/pharmaceutical industries.

• Maintaining an integrated, updated database on all medical treatment, training, pharmaceutical, research and production facilities.

American Medical Intelligence

The global health and medical landscape is not transparent. Part of the mission of the United States National Center for Medical Intelligence is uncovering this reality, enabling military leaders and policymakers to make fully informed decisions just like other analytical centres within the Defence Intelligence Agency.

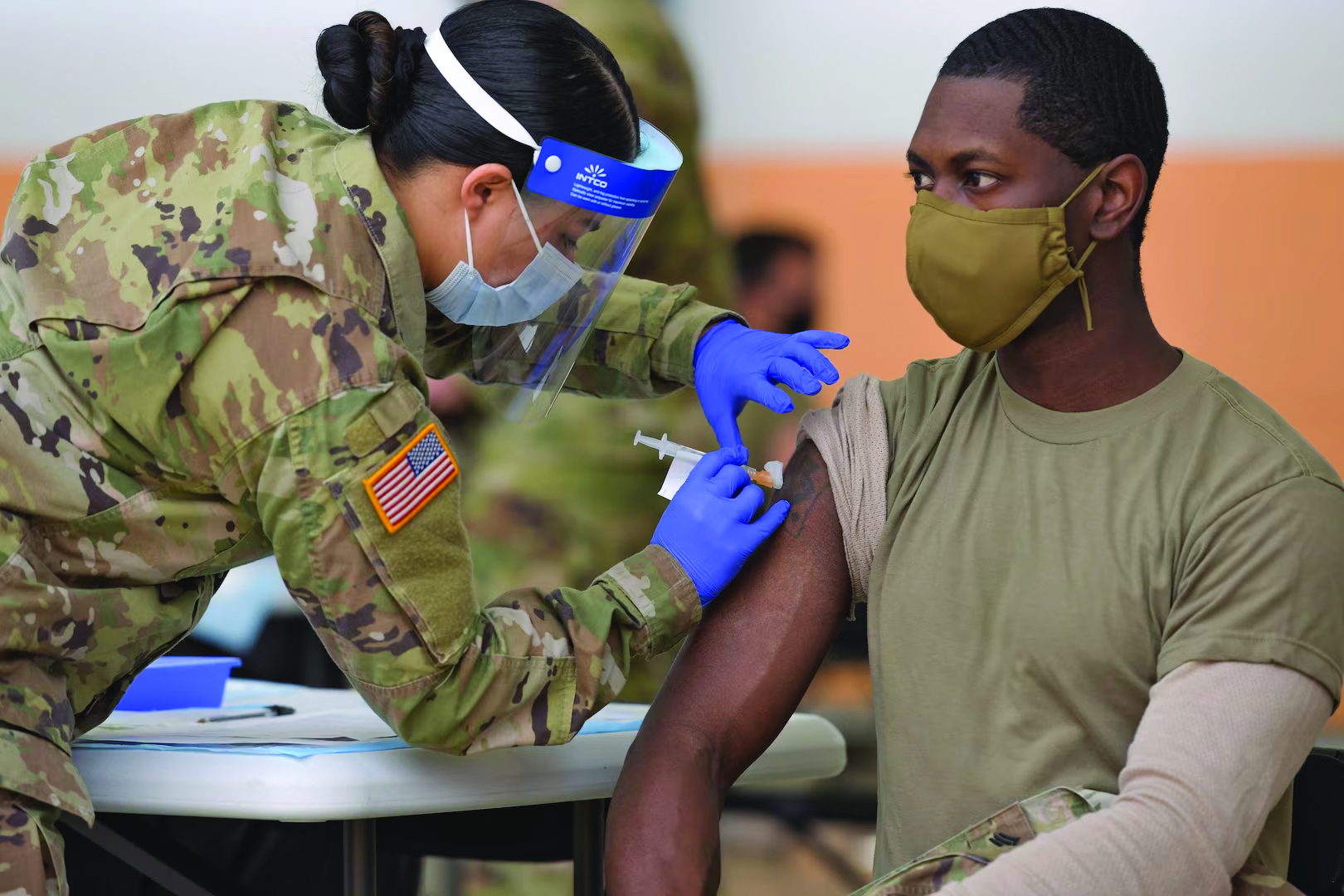

The need for medical intelligence emerged in World War II when the U.S. Army Surgeon General established a medical intelligence Division to support planning for military governance in new territories, by providing detailed guidelines on civilian public health and sanitation.

Medical intelligence products were part of formal war planning with health data integrated into the Department of Defence strategic surveys.

In 1956 the Medical Intelligence Division transformed into the U.S. Army Medical Information and Intelligence Agency which became part of the Defence Intelligence Agency in 1962.

After the Vietnam War and through the Cold War the role of medical intelligence diminished until it resurfaced again in 1992 as part of the Defence Intelligence Agency.

In 2000 the U.S. National Intelligence Council issued a unique report entitled “The Global Infectious Disease Threat and Its Implications for the United States,” which it quickly followed with a White House statement declaring HIV/AIDS and emerging and re-emerging infectious diseases a threat to national security, then naming diseases like Ebola, HIV/AIDS and multidrug-resistant TB and staph as direct threats to the United States. On July 2, 2008, medical intelligence became the purview of the National Center for Medical Intelligence where it remains until today, providing information on foreign health threats and capabilities including infectious diseases, CBRN threats, health infrastructure, health systems and sciences, life sciences, biotechnology and countermeasures. This centre examines long-term threats to DoD interests as well as opportunities. At the Center’s inauguration, its director Michael Mapples stated: “The National Center for Medical Intelligence is the vital link between protecting our forces and protecting the larger domestic health and this underscores the vital contribution medical intelligence makes to public health security.”

In April 2020, ABC News reported in an unconfirmed report that the White House had been warned of the impending COVID-19 outbreak in Wuhan, China, through a report by the National Center for Medical Intelligence.

During this pandemic, medical intelligence helped close knowledge and policy gaps related to COVID-19 by developing and delivering daily intelligence briefs on four main areas: epidemiology and infectious diseases; health care capabilities and infrastructure; policies and regulations; and diagnostics and therapeutics. All of this information contributed to decision-making and domestic policy development in responding to the pandemic. The use of medical intelligence in the strategy for responding to a future pandemic has proven to mitigate threats from epidemics more effectively and improve force health protection. The United States places its National Center for Medical Intelligence within its Defense Intelligence Agency. Placing disease surveillance activities strongly within the jurisdiction of military organizations, this trend toward militarization raises questions challenging the intertwining of medical and security issues and foreign policy.

»By: Retired Colonel Eng. Khaled Al-Ananzah (Advisor and Trainer in Environmental and Occupational Safety)