Future battlefields—land, air, maritime, space, and electromagnetic—are expected to become increasingly complex. This complexity is compounded by the intertwining and intricate cultural, economic, environmental, political, social, and technological contexts more than ever, making future battles fundamentally different from today’s.

Henri Bentégeat, former Chief of Staff of the French Army, underscores this by stating, “Waging war requires solidarity between political authority, military leadership, and popular support under all circumstances because military action is just one element of the comprehensive strategy, which includes financial and economic aspects.”

Furthermore, the sense of security and assurance that some armies once felt when facing a predictable enemy is now a thing of the past. Detailed contingency plans that were crucial for the defence of Europe and the Western world have lost their significance, as have the doctrines and training programmes designed to combat a known adversary. The world has shifted into a more chaotic and turbulent era, likely to become even more ambiguous, uncertain, and unstable over time. In this uncertain world, one thing is clear: warfare will become more complex.

The complexity of battlefields will significantly increase, particularly due to the asymmetric nature of threats, the rise of urban warfare, the obscurity of operational contexts, the expansion of battlefields, the interaction between technology and humans, and live media coverage.

In such a context, some countries have strived to maintain their military superiority and retain the initiative in increasingly complex and interconnected battlefields. They have developed the concept of cooperative multi-field and multi-domain combat. In the following lines, we will review the most important Western experiences and the Chinese and Russian experiences.

The Western Experience

The French Army has institutionalised the concept of cooperative multimilieux / multichamps operations (M2MC) or “multi-field / multi-domain combat”, notably by incorporating it into the French force doctrine (DEF). The concept of M2MC is limited to two main operations: large-scale targeting (CLS) and joint effects.

The United States is the only country that has fully realised the concept of M2MC, initially limited to a few operations that enforced cooperation between the military branches at the tactical level (especially amphibious, airborne and special operations, along with close air support). This concept has since evolved, reflecting the comprehensive approach illustrated below.

The Evolution of Multi-Domain Synergy for Cooperative Combat

In response to then-Deputy Secretary of Defense Bob Work’s desire to adopt a doctrine reflecting the strategy to counter the erosion of American superiority against Beijing and Moscow, the strategy of “Multi-Domain Cooperative Combat” (M2MC) was deepened.

This aimed to achieve “optimal convergence” of time and space for all capabilities across different environments and domains and redefined the principle of focus to prevent breaches and dismantle anti-access/area denial (A2/AD) capabilities in the event of armed conflict as well as achieve a decisive victory in the strategic competition battle through operations within the what is known as the “grey zone.”

The grey zone is a hybrid confrontation space before armed conflict, blending aggressive intelligence manoeuvres, electronic warfare, and influence strategy, particularly in the cyber environment.

In this context, the U.S. Army adopted the All-Domain concept based on the new Joint Warfighting Concept (JWC) and interoperability with allies.

The American philosophy of “Multi-Domain Cooperative Combat” (M2MC) can be summarised in the convergence of two principles: first, doctrinal and operational, extending the logic of Combined Arms Maneuver introduced recently in AirLand Battle; and second, technical, completing the logic of Network-Centric Warfare (NCW) to ensure the connectivity of military elements and units, maximising their power, enhancing information flow, and ensuring easy coordination and cooperation in achieving objectives.

The American vision combines the concepts of “Multi-Domain Operations” (MDO) and “Joint All-Domain Operations” (JADO) to ensure the synchronisation of its main systems across all domains, such as aircraft, ships, submarines, land vehicles, satellites, and missile systems, achieving full dominance of modern battlefields.

This enables commanders to make the best decisions quickly. MDO and JADO together aim for integration at all levels, including the lowest tactical level, allowing the disruption and destruction of enemy A2/AD capabilities. These are measures that slow the arrival of forces to the theatre of operations (A2) or hinder manoeuvres within it (AD), perfectly aligning with the American way of warfare.

The British Ministry of Defence presents its vision for Multi-Domain Cooperative Combat in its strategy named Multi-Domain Integration (MDI), which appears more mature than the American vision in several points. These include not only achieving M2MC in a narrow sense but also fostering cooperation between ministries, the British Army, allied armies, and their institutions. The UK’s M2MC strategy fits within its vision of achieving Integrated Operating Concept 2025, aiming for the UK to lead strategic movements globally rather than reacting to them by possessing the three pillars of power: influence, economy, security, and the synergy of their integration with military power.

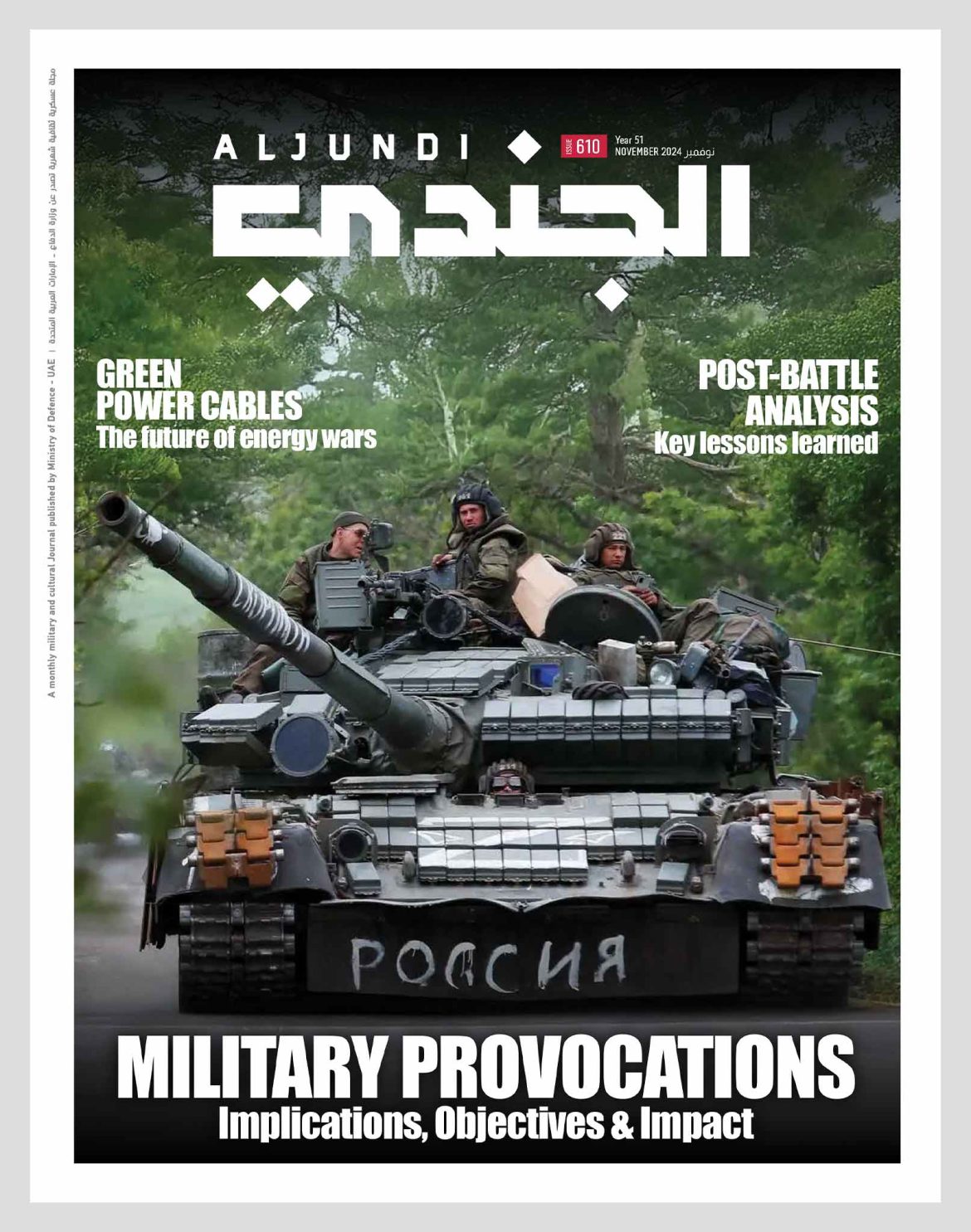

The Russian and Chinese Experiences

M2MC operations, meaning multi-domain operations, focusing on preventing the repetition of the U.S. method since the first Gulf War, which is systematic, large-scale airstrikes capable of decapitating decision-making centres.

The spectre of “lightning air war” against western and southern areas continues to shape Russian military plans. In this context, Russia developed cooperative combat called the “active defence” posture, integrating all means to weaken the opponent’s combat capability, including preemptive strikes.

However, the Russian idea goes beyond creating “anti-access zones”; it is rather a dynamic combining defence (attrition) and counterattack (annihilation and chaos), supported by a continuous series of hostile operations with deterrence operations. This is about the ability to inflict severe damage on the opponent, whether to its conventional forces or economic and political capabilities.

The continuous evolution and adaptation of M2MC concepts reflect the necessity for modern armies to operate effectively in increasingly complex and multifaceted battlefields. As technological advancements and strategic environments evolve, so too must military doctrines and operational strategies, ensuring readiness and superiority in future conflicts.

One of the key outcomes of the cooperative “active defence” strategy in the Russian Air Force (VVS) is its integration with air defence forces (PVO), and the addition of military domains under the name Aerospace Forces (VKS) in 2015.

Moreover, Russia continued to network its strike components to maintain its ability to reach and neutralise centres of power deep within its adversaries.

China, similarly to Russia, took the Gulf War as a starting point for its general military strategy, adopting an “active defence” posture designed by Mao Zedong. Recently, however, China has focused on how to prevent enemy military strikes from giving rise to an internal opposition force or creating a system-against-system The new Chinese integrative strategy emphasises preventing the enemy from decapitating or weakening the regime with a military strike that could create an internal adversary. Information and knowledge dominance are central to China’s strategy to counter these threats, achieving a form of “integrated general efficiency” in training, and going beyond coordination between military branches to unifying them in “integrated joint operations.”

The 2015 White Paper perfectly encapsulates this integrative military approach and its goals: information and knowledge dominance, precision strikes on strategic targets, and integrated operations to achieve victory (xinxi zhudao, jingda yaohai, lianhe zhisheng).

Unlike Russia, China’s asymmetry option is less structural but conditioned by the country’s economic and military superiority over its competitors, aiming for the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) to become a “world-class military” by 2050. China’s military modernisation does not follow a vertical and comprehensive plan for developing its capabilities but adopts a gradual approach, validated through the progressive enhancement of joint skills for specific tasks within increasingly large formations. This is done through an operational systems (OPSYS) framework capable of executing operations in an integrated and independent manner, such as the anti-aircraft OPSYS, the anti-landing OPSYS, and the OPSYS53 information combat program. These programs are activated according to the mission’s objective: island blockade, counter-blockade, amphibious assault, border counterattack, and anti-air raids.

China’s strategy revolves around the PLA’s ability to deploy forces assembled specifically for a campaign or mission, with multi-domain, multi-functional, and multi-dimensional capabilities, ensuring their integration through standardisation and unification within a joint command structure that integrates the staffs of various agencies in its operational area. Elements are also separated according to needs, employing a dynamic assembly and disassembly depending on the battlefield context and objectives.

Conclusion

There is no doubt that the shift to Multi-Domain Cooperative Combat faces short- and medium-term challenges, primarily the technical, doctrinal, and cognitive interoperability between military institutions and sectors of a single army and between allied armies, due to differing work cultures.

However, in the long term, the future promises the realisation of the “Multi-Domain Cooperative Combat” model as a new paradigm of command and control in military activities, linking all means of warfare in a web-like network for decision-making at various levels—tactical, operational, and strategic. This might lead to what American military studies researcher Max Boot envisioned: the command centre of armies might not be in the Pentagon, Kremlin, or a location in Beijing as traditionally known. Instead, it could be in an office in a skyscraper, with personnel not in military uniforms or traditional military hierarchy. The specialisation and job descriptions of these centre personnel might be of a new kind altogether, unfamiliar to us.

By: Dr. Wael Saleh, Expert at TRENDS Research & Advisory Center