For over two decades, geostrategic thinkers and military planners have been mesmerized by the growing challenge that anti-access and area denial (A2/AD) strategies and capabilities present to US military power. At the center of this debate are a range of capabilities that can be used to deny or constrain the entry of opposing forces into a given area of operations and subsequently reduce their maneuverability and effectiveness. The starting point of the A2/AD challenge, following a period of unparalleled military dominance by the United States, has been the diffusion of precision strike capabilities to US adversaries. China and Russia, in particular, have made major efforts to develop ever-widening A2/AD arsenals, which are central to their efforts to establish spheres of influence, that are isolated from US influence.

Central to these efforts is the ability to disrupt US efforts to amass forces in a theater of operations, in case of conflict. This requires the ability to cut or interrupt access to strategic infrastructure – such as bases, ports, and airfields – while limiting the ability of US forces to maneuver freely within striking distance. Although initially focused on the air and sea domain, US adversaries have increasingly widened their ambitions by developing A2/AD battle networks that seek to cut across the full spectrum of operations, including the land, air, sea, space, and cyber domain, as well as the electromagnetic environment.

The growing ability of China – and to some extent Russia – to develop cross-cutting A2/AD networks has been interpreted by some as spelling the end of a golden era of US power projection. In light of these developments, some have argued that China is making steady progress shutting the US out of the Western Pacific and East Asia theaters. The argument is that by deploying a dispersed network of medium and long-range missiles, precision sensors, space, aerial and naval assets, and long-range standoff capabilities, China is able to restrict US access to strategic waterways, effectively turning them into a Chinese lake.

Limitations of the A2/AD Debate

The A2/AD challenge has had a galvanizing effect on the US military establishment, resulting into vast resources being allocated to develop capabilities and concepts that would allow the US to penetrate China’s A2/AD umbrella. In the process, A2/AD has turned into an all-encompassing buzzword that has come to describe a vast array of capability and strategies, in the process losing some strategic purpose.

Thus, former US Chief of Naval Operations, Admiral John Richardson, argued that A2/AD serves only a limited purpose as a general buzzword, but lacks precision and definition:

“To some, A2AD is a code-word, suggesting an impenetrable ‘keep-out zone’ that forces can enter only at extreme peril to themselves. To others, A2AD refers to a family of technologies. To still others, a strategy. In sum, A2AD is a term bandied about freely, with no precise definition, that sends a variety of vague or conflicting signals, depending on the context in which it is either transmitted or received.”

More concretely, Richardson highlighted the following three problems with A2/AD:

• Different theaters present different challenges and adopting a “one-size-fits-all” approach to A2/AD is not helpful. Instead, there is a need to closely tailor strategies and capabilities to the specific theater and context, and the specific array of capabilities and technologies of adversaries.

• A2/AD in and of itself is not a “novel” concept. Military strategy in every age has been about denying your opponent access to strategic territory and constraining his movement.

• “Access denial” is in itself a misleading terminology and concept, as it suggests that this is a strategic objective that is achievable, whereas in reality it is more likely to remain an aspiration.

Other critics have zoomed in on the fact that in and of itself, A2/AD does not change the military balance of power – and that for the time being Russia and China remain at a clear disadvantage vis-à-vis the US. While it is unrealistic for US adversaries to use A2/AD to pose a direct military challenge to US forces, it allows them to exploit a temporal advantage (ETA) to seize an objective and facilitate a political outcome.

Using the ETA as the starting point, recent analysis has sought to shift the focus away from A2/AD as aiming to create “angry red bubbles” to four distinct processes seeking to shape the temporal advantage:

1 Information degradation and command (or cognitive) disruption (ID/CD), which seeks to provide US adversaries a cognitive advantage by attacking US systems in space, cyber, and the electromagnetic spectrum.

2 Contesting theater access and maneuver (CTAM), which seeks to limit or delay access by the US to contested areas by raising the associated risks, often using inexpensive, low-tech technologies.

3 Degrading sustainment, logistics, and mobility (DSLAM) is aimed at interrupting or diminishing the complex supply and logistics networks that are crucial for US operations.

4 Strategic actions to deter, coerce, and terminate (SADCAT), which can involve a wide spectrum of capabilities, from attacks on commercial assets to the threat of nuclear weapons in order to deter escalation and end a potential confrontation to the advantage of the adversary.

Reconceptualizing and disaggregating A2/AD along these fields suggests a focus on different capabilities and concepts than the more static initial conceptualization of A2/AD as focused on “area denial”.

Outside-in: Beating A2/AD at Range

Military analysts have developed a broad range of approaches that seek to deal with the amorphous A2/AD challenge. An early example of this is the “outside-in” enabling operational concept, which relies on dispersed forces at distance to puncture and degrade the adversaries’ A2/AD capabilities before re-establishing US ability to maneuver within theater and to ultimately restore in-theater superiority. This process relies on three distinct lines of operations in order to deal with A2/AD:

1 The development of an enabling operational concept that revolves around dispersing US forces and military assets outside the reach of the anti-access threats of a military adversary. This also requires developing key local/regional partnerships, developing logistics concepts, and setting conditions that would allow for the deployment of US forces to meet probable challenges.

2 The second stage of this concept evolves around operating from range in order to degrade and reduce the effectiveness of any A2/AD assets, undermine the opponents ISR capabilities, and successively punch holes into the adversaries offensive and defensive operations.

3 The third stage evolves around the re-establishment of local air, maritime, and land superiority in pockets, in order to enable the force deployments and start operations in theater.

This step-by-step approach revolves significantly around a local, rather than a temporal, view of A2/AD. The focus is on pre-positioning forces strategically, developing greater range and impact than the adversary, and deploying protected bubbles from which large operations can be prepared. This suggests the development and deployment of a specific mix of capabilities, including long-range penetrating missiles and bombers, carrier systems, long-range UAVs, precise and impactful stand-off ammunitions, cyber-capabilities, and theater missile defenses along other force protection capabilities. While this approach might be effective in specific theaters, such as the Strait of Hormuz, or for specific limited objectives and less sophisticated adversaries, it is less clear that it provides a winning strategy in a contest with more sophisticated adversaries that seek to achieve well-defined limited objectives.

Critics of concepts such as the outside-in approach point out that they largely rely on the US maintaining an edge on legacy systems that have long become appropriated by sophisticated adversaries such as China and Russia, including systems such as stealth fighters and precision missiles, and that it underestimates the temporal element and systems focus that are central to new and more sophisticated uses of A2/AD.

Mosaic Warfare: 21st Century Maneuver Warfare

In response to the challenges, the Defense Advanced Research Project Agency (DARPA) has come up with a range of decision-centric warfare concepts, such as multi-domain operations and mosaic warfare. The focus of these concepts is to enable the US military to conduct multi-domain maneuvers against adversaries that possess precision-strike capabilities. Mosaic warfare starts from the premise that the present composition of US forces that rely on large manned multi-mission units such as ships and aircraft are monolithic, predictable, and slow, enabling adversaries to anticipate US actions. They also provide an ideal target for the sophisticated A2/AD systems that are being deployed by Russia and China.

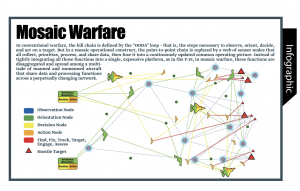

To counter this, DARPA argues that the US should develop a form of decision-centric warfare that disaggregates some of these large platforms and instead relies on much smaller units. These smaller units are networked, flexible, and can be rapidly configured and reconfigured in order to take on different roles and characteristics. While integrated into a larger system, units act independently, with commanders not having complete situational awareness but embracing the fog of war. Functions are disaggregated and spread among a multitude of manned and unmanned platforms that share data and process functions across a perpetually changing network that confuses and disorients the enemy.

To carry out this kind of operations, mosaic warfare suggests the development of very different kinds of capabilities than those required for a more classical outside-in approach. In particular, mosaic warfare suggests the deployment of a range of autonomous systems that can be deployed in man-machine configurations relying on cheap, fast and flexible systems that can be easily scaled. The other capabilities that mosaic warfare prioritizes are AI-enabled systems that help to empower mission command. By drawing on AI to enable fragmented decision-making, units are more independent, and less detectable.

Rather than addressing A2/AD at range and through incremental improvements of legacy platforms, mosaic warfare therefore seeks to provide more flexible answers that reflect the diverse nature of the challenge. Moreover, unlike the outside-in approach, mosaic warfare is not focused on attrition and destroying the enemy’s forces. Instead, it represents a form of 21st century maneuver warfare that aims to dislocate and disrupt enemy operations, in order to prevent him from achieving his objectives. This can involve small flexible ground forces to establish beachheads in theater, to open gaps in the A2/AD infrastructure of enemies or tackling the enemies A2/AD systems directly. Mosaic warfare also emphasizes the temporal element of A2/AD and is less focused on seizing and controlling ground. While the two approaches represent different views on how to better counter the A2/AD challenge they are located on a continuum of possible options. As the nature of the A2/AD challenge to US forces continues to change, it can be expected that this continuum of options will continue to widen as well.

» By: Dr Timo F Behr

(Co-Managing Director of Westphalia Global Advisory & Subject Matter Expert at The Hague Center for Strategic Studies)