Throughout history, learning, analysing, and extracting lessons from past experiences have been integral to societal progress. Humanity has continually sought to refine what has worked and identify alternatives for failure, whether through systematic methods or intuitive thinking. The rapid advancements of the 21st century—especially in technology, data accumulation, and the swift flow of information—have placed societies in a race for survival. The victors in this race are those who can learn and adapt faster. As a result, learning and extracting information has become essential for any organisation that seeks not just to survive, but to thrive—an approach aligned with Darwin’s principle of “survival of the fittest.”

Organisations are driven to learn and improve for two primary reasons: first, to avoid past mistakes, and second, to achieve greater success from the outset. This process builds confidence in employees, enhances their ability to recover from failure, and fosters institutional excellence.

In recent years, there has been a growing emphasis on applying organisational learning and feedback principles, particularly within public sector institutions, to improve services and strategic outcomes. Military institutions have been at the forefront of these developments, having established formal military learning processes throughout history.

Since the 1980s, technological and conceptual advancements in organisational learning have encouraged the creation of structured and continuous learning systems within the military, now commonly referred to as “lessons learned” programmes. These systems have been greatly developed during military campaigns in Iraq and Afghanistan.

As former US Marine Corps General James Mattis stated, “There is no reason to send troops into combat and have them killed when a lesson learned just a month earlier can be sent to a commander who can use it for training.”

The military’s lessons-learned programmes exist to enhance readiness and improve combat capability by leveraging the experiences of commanders and soldiers. A validated lesson learned offers evaluative insights that lead to improvements in military operations or activities at the strategic, operational, or tactical levels.

The Concept of Lessons Learned:

Lessons learned are experiences drawn from previous activities that should be actively considered in future actions and behaviours. According to NASA, a lesson learned is “knowledge or understanding gained from experience,” which could be positive, as in a successful test or mission, or negative, such as an unfortunate incident or failure. The lesson must be significant in its real or potential impact on operations, factually and technically accurate, and applicable in its ability to identify a design, process, or decision that reduces the likelihood of failure or enhances a positive outcome.

Similarly, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s (OECD) Assistance Committee defines lessons learned as “findings based on evaluation experiences from projects, programmes, or policies that are stripped of specific circumstances and broadened to apply to wider situations.”

Often, lessons learned highlight strengths or weaknesses in planning, design, and execution, which affect performance, outcomes, and impact.

In the military context, conducting post-action analyses and extracting lessons learned after operations (whether combat or training) requires commanders to extend the standard review of lessons post-action. This may involve event reconstruction or having individuals present their roles and perceptions of the event, depending on the situation and the time available.

Since 1985, the US Army’s Center for Army Lessons Learned (CALL) has overseen the military’s lessons learned programme, identifying, analysing, publishing, and archiving key lessons and best practices. To enhance the ability to learn from experiences within the military, various data collection methods are employed (followed by analysis, dissemination, and archiving).

Based on the data collected, the sequence of events is reconstructed. This process typically involves after-action reviews, in-depth individual and group interviews, and regular examination of relevant documents, such as operational orders, logs, and aerial photos. However, some tactical decision-making processes cannot always be easily reconstructed based on collected information alone.

Learning from the Past:

The concept of lessons learned, or learning from experience, often referred to as post-battle analysis, is widely used to describe the people, processes, and activities involved in improving outcomes by reflecting on past experiences. In any organisation, the principle behind lessons learned is that a formal approach to learning can help individuals and the organisation as a whole reduce the risk of repeating past mistakes while increasing the likelihood of repeating successes.

In the military, lessons learned are an essential part of an organisation’s credibility, capability, and adaptability in warfare. By focusing on reducing operational risks, increasing cost efficiency, and enhancing operational effectiveness, lessons learned contribute to the constant evolution of military tactics and strategies. These insights can be drawn from a range of activities, including operations, exercises, training sessions, and even routine daily events.

Traditionally, lessons-learned programmes have been used to improve organisational performance and have typically been “commander-led” initiatives—tools employed by leadership in a top-down approach. However, there is another equally important aspect often overlooked: bottom-up organisational learning.

This approach encourages the sharing of information about common problems and solutions across a community of practice, enabling the broader organisation to learn from each other’s experiences. The aim is to avoid wasting resources and prevent the repetition of the same mistakes.

The US military, with its various services, personnel, and support agencies, fits the model of a large, complex organisation with numerous sub-organisations. Within this large and diverse structure, leaders instinctively strive to ensure that those under their command learn from past mistakes to avoid repeating them, while also seeking out best practices to gain an edge over potential adversaries.

In this sense, commander-led lessons-learned programmes have existed since the earliest days of organised conflict. However, sharing failures within a military environment—where hierarchy is deeply ingrained, and competitiveness is high—does not come naturally. Military organisations often struggle to openly share failures for collective learning. Yet in a dynamic environment characterised by evolving threats and tight financial constraints, striking a balance between the need for commander-led programmes and the timely sharing of knowledge across the institution is critical.

The US Marine Corps Lessons Learned Centre plays a pivotal role in this process by collecting, analysing, publishing, and archiving a wide range of lessons learned materials. These include observations, insights, trends, and post-operation and post-training reports. The centre’s work supports both training and operational planning, as well as the broader process of developing combat capabilities.

Its primary focus is on tactics, techniques, and procedures that are of immediate relevance to operational forces, helping to identify gaps and best practices. The centre also recommends solutions based on key military doctrines, including strategy, organisation, training, equipment, leadership, personnel, and facilities. By doing so, the Marine Corps Lessons Learned Centre enhances the preparedness and combat effectiveness of the entire force.

Best Combat Practices:

The US Army’s Centre for Army Lessons Learned (CALL) leads the programme for collecting, analysing, and disseminating lessons learned to fill capability gaps, enhance readiness, and support operational updates.

To accomplish this, the Army’s annual plan involves gathering lessons from tactical to strategic levels, analysing root causes, identifying trends, and coordinating with stakeholders in the lessons learned community before developing products. These multimedia-based products are shared through various print and electronic formats and stored in a central repository—an online shared lessons-learned information system.

As emerging issues are identified, CALL integrates these into the Army Lessons Learned Forum to facilitate continuous development, improvement, and adaptation with both material and non-material solutions. Recently, CALL launched the Best Practices Initiative to help improve the Army by increasing the submission of best practices from soldiers and units, and sharing this information with the broader force.

Soldiers can submit their individual or collective best practices. The Army defines best practices as changes in how tasks are performed that improve individual, unit, or organisational performance, even if these changes have not been fully implemented across the entire force.

Additionally, CALL is responsible for reviewing and disseminating best practices, and this responsibility falls under the Army Training and Doctrine Command’s Centre of Excellence. Analysts at CALL review the submitted best practices through an online platform before publication. This review process may involve dialogue between the analyst, the author, and/or the unit to ensure the proposed practices are sound and can be replicated in similar units. The director of Lessons Learned for the US Army sees the initiative as a natural progression of the work already being done. “We know that soldiers and units are agile and adaptable. Our soldiers come up with great ideas to solve problems or improve how they perform their jobs, whether in the field or a deployed environment,” the director explains. CALL collects lessons and best practices daily and continues to share this information as part of an official process. The aim is to create a more responsive mechanism for soldiers to provide direct input and share their ideas quickly across the force. A historical example of best practices dates back to World War II, following the Normandy invasion. The US forces encountered the physical challenge of the French bocage—thick hedgerows that were nearly impossible to penetrate.

The Nazis used these natural barriers as cover and defences, rendering them nearly impenetrable to US tanks without exposing them to enemy fire. The stalemate persisted until a young cavalry scout officer suggested attaching makeshift prongs to the front of the tanks, allowing them to cut through the hedgerows and advance.

More recently, an example of best practices in action can be seen in the development of devices to counter improvised explosive devices (IEDs) during operations in Iraq. Soldiers in a forward support battalion designed a device to defeat infrared-triggered IEDs.

Additionally, input from soldiers led to modifications in Mine Resistant Ambush Protected (MRAP) vehicles, ultimately saving lives and improving mobility. Brigadier General James J. Mingus remarked, “We know that innovation and best practices usually come from the lowest levels. This programme gives soldiers the opportunity to share their ideas with others. These ideas ultimately help the Army train and execute more effectively.” To highlight the individual soldier and unit initiative and enhance the sharing of best practices across the Army, CALL recognises outstanding field submissions quarterly, awarding units and individuals with certificates of achievement. These certificates may earn promotion points for qualified specialists and sergeants.

Moreover, CALL leads change by identifying, collecting, analysing, publishing, and archiving lessons and best practices while maintaining global situational awareness to facilitate knowledge exchange. This enables the Army and its partners to adapt and remain competitive in modern warfare.

NATO and Lessons Learned:

Lessons learned play a fundamental role in NATO’s military operations, enhancing credibility, capability, and adaptability in combat and war development. Insights can be drawn from any activity, such as operations, exercises, training, and daily events. According to NATO’s Joint Operations Doctrine, “The purpose of the lessons learned process is to learn efficiently from experience and provide validated justification to modify current methods of operation to improve performance.” NATO defines its lessons-learned capability as a process that provides commanders with the structure, tools, and methods to capture, analyse, and act upon any issue, communicating and sharing results to foster improvement. The aim is to learn from experience efficiently and provide sound reasons for modifying current procedures to enhance operational performance in future missions.

NATO’s lessons-learned capability comprises several key elements: leadership, mindset, structure (such as lessons learned by staff officers), processes, tools, training, and information sharing. For the alliance to succeed as a learning organisation, it must have a robust and effective lessons-learned capability. This involves having the right structure, processes, tools, and training to capture, analyse, and implement corrective actions on any issues, and to share the results for continual improvement. Equally important is fostering the right mindset across the alliance to ensure that issues are captured and addressed through a formalised lessons-learned process. True organisational learning only occurs when leadership prioritises the lessons learned activities and follows up with their personnel to ensure that the institution is, in fact, learning.

The lessons learned capability allows militaries to significantly improve their ability to translate localised adaptations made by forces in deployment into broader organisational innovation and learning. However, lessons-learned processes within many NATO member states are still developing, and they vary in their institutional structures and effectiveness in realigning military operations with the campaign and operational requirements.

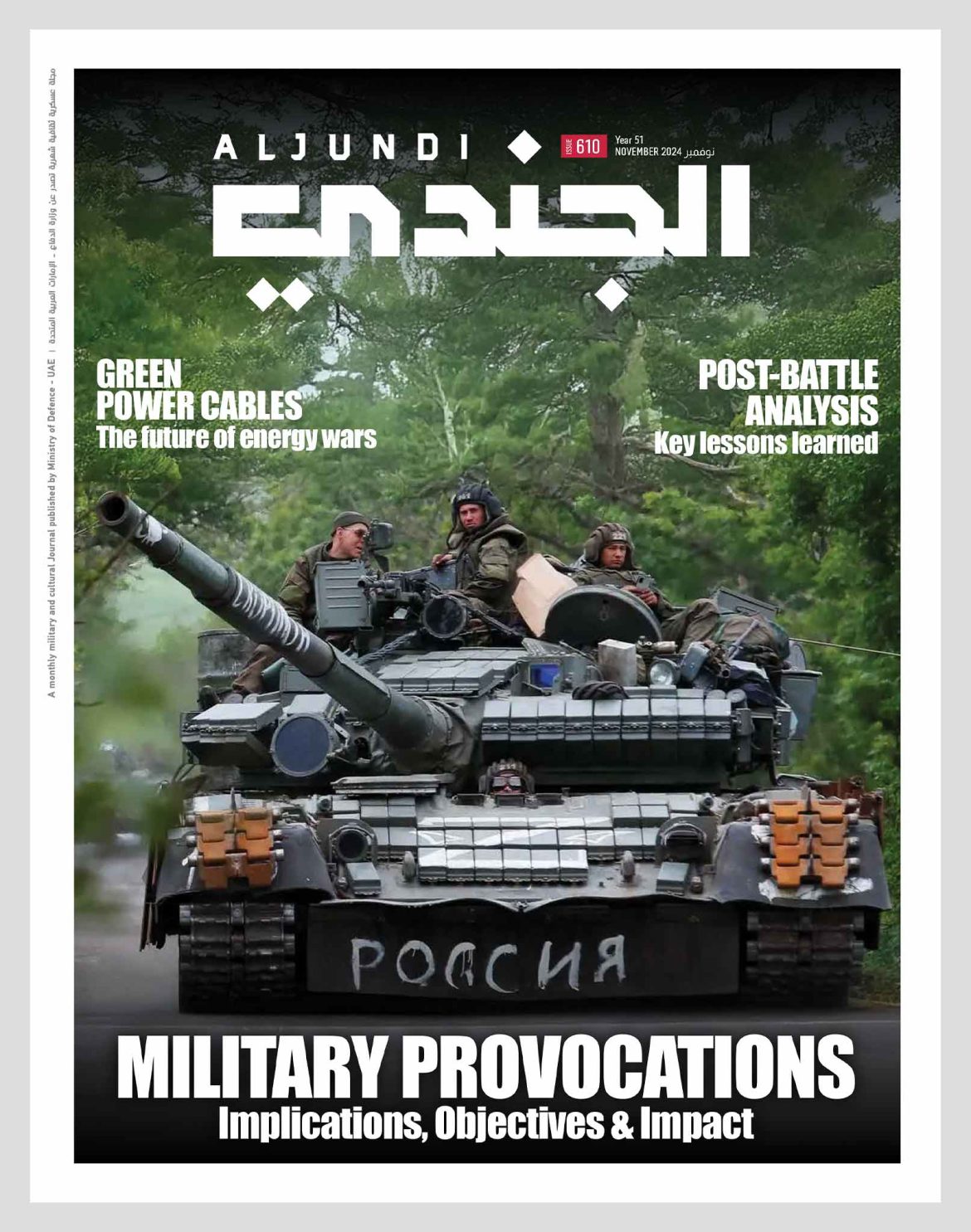

Lessons Learned from the Russia-Ukraine War:

In a research project titled Key Findings and Lessons Learned from the Russia-Ukraine War conducted by researchers from the US Army War College in 2024, seven key lessons were identified. These cover doctrinal, operational, technological, strategic, and political issues related to the war. The Russia-Ukraine conflict offers critical insights into how future conflicts may be influenced by the abundance of digital information and the maturation of artificial intelligence (AI).

For US Army intelligence, one of the central aspects of this conflict is the emergence of a commercial intelligence-like service system. Companies like Palantir, Planet Labs, BlackSky Technology, and Clearview AI are driving this system forward. Ukraine has embraced these actors and is leveraging the potential of their services to manage the growing volumes of information. AI is a crucial area of development, with applications in targeting, battle tracking, voice recognition, translation, data management, autonomous aviation, disinformation countermeasures, and cybersecurity.

The study highlights four key implications for US forces:

Technological Trends in Military Operations: The Russia-Ukraine war underscores the importance of technological trends shaping the operational environment. Even if the US Army intelligence apparatus does not adopt them, these technologies are available to allies, partners, and adversaries.

Integration of Sensors: The war illustrates how sensors can be integrated at both tactical and operational levels as part of a continuous and flexible collection network.

Utilisation of Open-Source Information: The conflict highlights how the US Army can benefit from unclassified information sources to enhance integration with allies and partners.

Diversity of Open-Source Information: The diversity of unclassified information sources improves intelligence analysis, spurs innovation, and helps forge connections with both local and foreign audiences. ●

» By: Retired Colonel Eng. Khaled Al-Ananzah (Advisor and Trainer in Environmental and Occupational Safety)